Longitude, first published in 1995, is a best-selling, award-winning book about how Europeans figured out how to determine longitude at sea during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Longitude, first published in 1995, is a best-selling, award-winning book about how Europeans figured out how to determine longitude at sea during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

As early as the time of Columbus, Europeans relied heavily on sea travel for trade, defense, and exploration. As the centuries rolled on, naval power only grew in importance. But there was a big problem. While mariners could calculate their latitude with a high degree of precision, their ability to determine longitude was close to zero. This meant mariners had to estimate or sometimes outright guess where to steer their ships, adding days or weeks to the journey.

Even worse, miscalculating longitude often brought ships perilously close to shallow water or land — sometimes with catastrophic results. The story of Longitude begins in 1707, when English Admiral Sir Clowdisley Shovell’s returning fleet rammed into islands off the southern tip of England, losing four warships and nearly 2,000 men. They had miscalculated their position. Sir Shovell, incidentally, survived the shipwreck, only to fall asleep on the shore from exhaustion and be murdered by a local woman so that she could steal his emerald ring.

This disaster led to an all-out quest in England and throughout Europe to find a reliable method of determining longitude. The book goes on to trace the progress of the competing approaches, the practical and personal struggles of the inventors, and the sometimes helpful, sometimes harmful interplay between science and politics in the development of a practicable solution. The story is full of drama, wonderful written, and full of beautiful illustrations, diagrams, and portraits.

Basically there were two competing approaches to solving the problem of longitude. One involved fixing longitude by measuring the movements of the moon, stars, or other heavenly bodies. The other involved using a clock. Think time zones: if you know the local time compared to a standard, such as the time at the port from which your ship departed, you can deduce your longitudinal position.

Each method had strengths and weaknesses. The astronomical approach involved complex calculations, and the careful, expert use of navigational devices such as a sextant. In addition, many of the movements of heavenly bodies were not predictable in those days, although great progress was being made that eventually led to astronomical positioning systems that were reasonably accurate. Finally, cloudy weather, the position of the earth in its orbit, daylight, and other factors made it impossible to take readings at certain times.

The clock — or chronometer, as seafaring clocks eventually became known — also had its share of problems. In the early 18th century, clocks were nowhere near precise enough to keep accurate time on land, let alone on sea, where harsh, extreme and changing environmental conditions, coupled with intense movements of the ship, would wreak havoc on moving parts. But even after clocks with excellent precision and durability were produced — a feat many thought impossible — their cost was far greater than that of the charts and tools used for astronomical calculations. However, clocks had the great advantages of being easy to use and usable 24/7 regardless of conditions aboard ship.

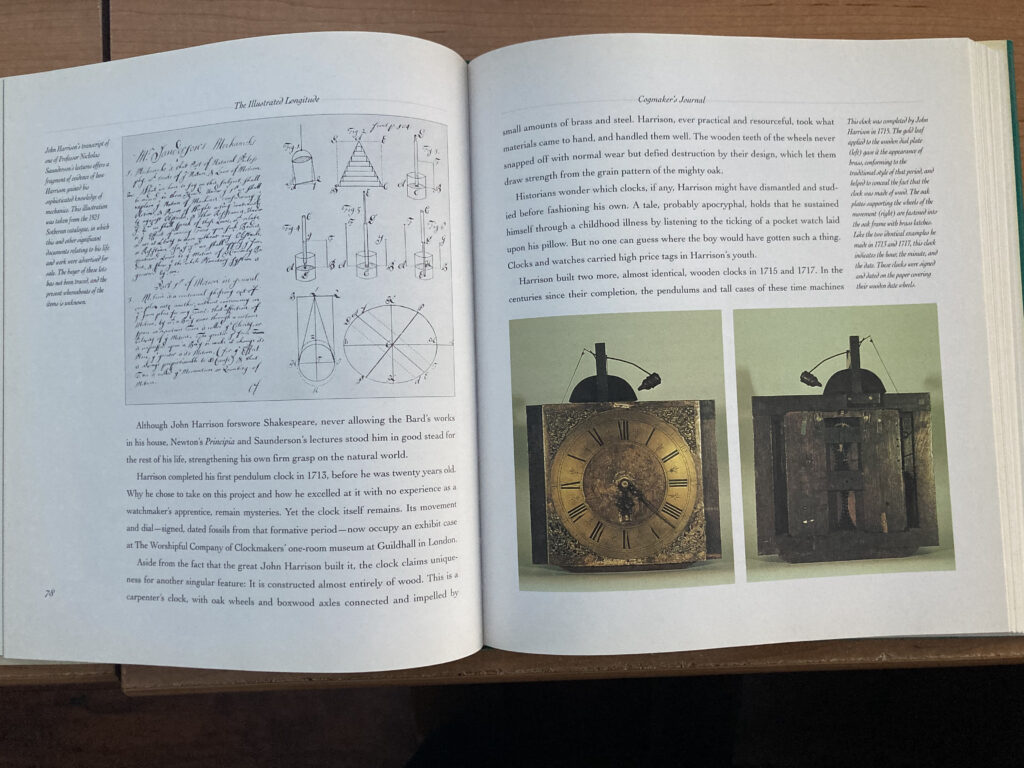

The hero of Longitude is John Harrison, an English carpenter-turned-clockmaker of humble origins who made the invention of a seaworthy clock his life’s work. He combined a remarkable genius for design and meticulous attention to detail to create a series of clocks over several decades. In addition to the pure joy of invention, Harrison was strongly motivated to win the £20,000 prize (over $2 million in today’s money) offered by Britain’s Board of Longitude. The Board was formed and its prize offered in 1714; Harrison’s winning clock, “H4,” made its successful test run in 1761-2, and the Board finally coughed up the last of Harrison’s prize money in 1773, when Harrison was 80 years old.

Along the way, Harrison had to fight Board bureaucracy, competition from clockmakers who were less talented but more persuasive (Harrison lacked tact and patience, and apparently could barely write a coherent sentence), as well as political maneuvering from inventors and vested interests pushing for an astronomical solution to the problem of longitude.

If you have any interest at all in naval exploration, astronomy, industrial design, European history, or just love an exciting story about a topic that seems rather dull on the surface — this book will provide a great deal of enjoyment.