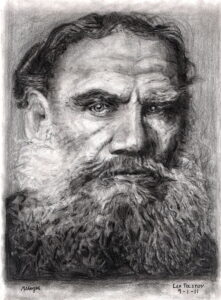

Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art? Translated by Richard Paver and Larissa Volokhonsky

What Is Art? Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) spent 15 years mulling over the question before finally publishing his profound essay of that title in 1897. Today’s readers may find many of his conclusions utterly shocking — for example, that the works of Shakespeare are not art and that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony amounts to “artistic gibberish.” But he makes a convincing case.

Tolstoy begins with a lengthy explanation of why art cannot be defined in connection with beauty. He does a masterful job of taking us through the various conflicting, confusing, and often ridiculous theories of beauty that have come down through the ages. In Tolstoy’s time, art was widely supposed to be beautiful in some (however vaguely defined) way. Today, of course, people routinely create and value works of ugliness and regard them as art.

Tolstoy then reveals the true definition of art — and this is where things get interesting to a modern reader. Essentially, Tolstoy defines art as the communication of feelings. The true artist creates a work of art only when he experiences a feeling he is compelled to share. According to Tolstoy, when art is successful, the artist “infects” someone with that feeling, resulting in a communion among the artist and all those who are affected. Art may be good or it may be bad. When art is good, it communicates feelings that nurture and advance the religious consciousness of that culture. When art is bad, it communicates feelings that undermine the religious consciousness. When art is successful, it communicates the feeling to many people.

Why, then, does Tolstoy conclude that Shakespeare and many others whom we regard as brilliant artists are not artists at all?

Why, then, does Tolstoy conclude that Shakespeare and many others whom we regard as brilliant artists are not artists at all?

At some point in history, European elites ceased to believe in the teachings of “church” Christianity, which Tolstoy considers a corruption of Christ’s actual teachings but which nevertheless served as the basis of the religious consciousness of the people. At this point, elites abandoned the idea of art as the means of raising religious consciousness — because they no longer had a religious consciousness — and began to view art purely as an amusement through which they could indulge and affirm their amoral inclinations. Artists were paid to produce paintings, plays, operas, works of fiction, etc., that reflected and glorified their decidedly non-Christian attitude that life is meaningless, and that lust, power, and pride are the most fitting themes for creative works.

Such works, created to amuse elites, did not spring from the desire of an artist to share a feeling; instead, the artist became a professional, a hired gun, whose creations became mechanical and formulaic. These works were inevitably artificial and corrupting, and in no way could be considered true art. Furthermore, because these works were created to please decadent elites, they were incomprehensible to the masses, who, unlike elites, retained their religious consciousness. Thus Tolstoy considers the works of Shakespeare, Beethoven (his later compositions in particular), Wagner, Goethe, and many others, as creative efforts perfectly fitting this description.

Tolstoy does not consider all esteemed creators to be false artists. He admires the work of Dickens, Victor Hugo, W. Mozart, Dostoevsky, among several others.

Tolstoy views false art as extremely dangerous to society. A steady diet of false art intensifies the corruption of the elites to the point where they are unable and unfit to manage the affairs of government and society. In addition, such art creeps into the consciousness of the masses — particularly in urban environments where the masses have already been corrupted to a very great extent — undermining the religious consciousness, something that if unchecked would eventually completely ruin life on an individual and collective level.

Tolstoy believes it is the main priority of artists and elites to restore art to its proper and all-important place as a mechanism by which the feelings that inspire religious consciousness are shared throughout the community. In the essay, he lays out how this can happen, and also, quite interestingly, offers a highly detailed description of what true art and effective art look like.

Tolstoy believes the best art is understood by the greatest number of people for the longest period of time. And the theme of this art?

“The religious consciousness of our time, in its most general practical application, is the consciousness of the fact that our good, material and spiritual, individual and general, temporal and eternal, consists in the brotherly life of all people, in our union of love with each other.”

Tolstoy takes universal brotherly love to be the central and overarching teaching of Christ, as well as of other spiritual leaders throughout history. This teaching, in his view, is the unadulterated, pure Christianity that has gotten lost among the accretions developed over centuries of “church” Christianity. But Tolstoy seems to believe that mankind is on a journey of spiritual progress, and seems hopeful that mankind will shed the accretions, that art of the future will again become genuine, and that humanity will see the corruption of the elites for what it is and rise up decisively against it.

Tolstoy makes his case with impressive detail, erudition, clarity, and careful, methodical reasoning. In particular to readers of this time, his insights about art and non-art, the cultural rift between elites and the common people, and his assessment of the elite mentality in general are disturbingly accurate and enlightening

Nevertheless, Tolstoy’s essay is not without problems.

Tolstoy writes as if non-art had reached rock-bottom in his time, that it could not possibly become more corrupt in its pornographic, narcissistic, materialistic, and violent character. How could he have foreseen the way in which recorded music, radio, television and the internet have accelerated, streamlined, and unified the transfer of non-art communication from corrupt elites to the mass audience? Tolstoy observes the sharp difference between popular art, which is true art produced by the people, and the non-art that is regarded as high art by the elites. But does this distinction still apply? It seems quite clear that the bulk of today’s so-called popular visual art, TV programming, rock, rap, video, Hollywood movies, etc., is not popular at all; instead what is peddled as popular are works created at the behest of elites and under the supervision of elites, for the purpose of validating and spreading their worldview.

It also seems hard to accept today that we are evolving spiritually, morally, religiously, or in any other way. It seems instead that are on the downside of yet another historic cycle of growth, maturity, and decay. At the time Tolstoy wrote What Is Art? the concept of evolution was widely accepted and widely applied. Even Tolstoy, original and fiercely rationalistic though he was, may not have been fully immune to the evolutionary mindset of his time. But I wonder: if Tolstoy had written What Is Art? after World War I, after World War II, after Hiroshima, after Stalin, after Mao — would he still have felt we are on a path marching anywhere near an art based on universal brotherhood?

A further difficulty is Tolstoy’s overall insistence on an ultra-simplified Christianity that accepts the teachings of Christ, but none of His divinity. Tolstoy’s is a faith without the need of faith. Chesterton said something to the effect that Catholic theology is complex because life is complex. Simple solutions won’t do. Today, for instance, there are people who want to see police forces abolished, as well as people who defend the police. Both types may feel they are acting in the interest of universal brotherhood. Who, then, decides which art is true art — art that depicts police as villains or that which depicts them as heroes? And there are many other examples.

To Tolstoy, at least in this essay, moral decisions seem clearcut, but in real life they never are.

Nevertheless, What Is Art? is an excellent warning, even today — perhaps especially today. Tolstoy’s solutions and theology may be open to question, but his assessment of cultural conditions is sound now as it was then. By reading this book, you will better understand what art actually is and isn’t, better understand why the programs you see on TV communicate the feelings they do, better understand why it is essential to stop consuming all of this non-art, and finally, better understand why and how to combat the destabilizing and dehumanizing effects of non-art in our culture, communities, families, and souls.

Postscript: The Side-Splitting Humor of Tolstoy

The book, incidentally, is not without humor. I don’t know if Tolstoy intends to be funny, but his lengthy description of attending a Wagner opera in Moscow, as he describes the inane plot in minute detail and with ever-growing dismay, is no less amusing than Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd locking horns in What’s Opera, Doc.

“Somehow I managed to sit through the next scene with the entrance of the monster, accompanied by bass notes interwoven with Siegfried’s motiv, the fight with the monster, all the roaring, the flames, the brandishing of the sword, but more I could not endure, and I rushed from the theatre with a feeling of revulsion I still cannot forget.”

A better description of Wagner, and the right reaction to it, there could not be.

In this essay Tolstoy remarks in passing that with a few exceptions, his own art does not fit the definition of true art. His fiction beginning slightly earlier and until his death was his attempt to follow his own advice. This later work, remarkable in its clarity and simplicity, is excellent.