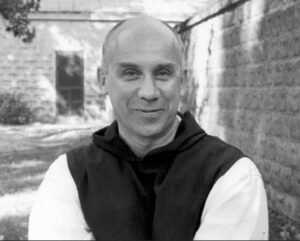

Thomas Merton (1915-1968) was a unique literary figure in the 20th century — perhaps so over a much longer span of time. A young man of letters living in New York City with a promising future as a poet and novelist, he decided — to the shock of all — to become a monk in a Trappist monastery in Kentucky, the Abbey of Gesthemani. The Trappists are a branch of the Cistercians, a strictly observant contemplative order whose members withdraw from the world, living a life of solitude, prayer, contemplation, and physical labor. Nevertheless, after joining the order Merton was ordered to continue writing, as his great talent was obvious to his superiors.

One of Merton’s first published works, The Seven Storey Mountain, is an account of his early life and decision to become a Trappist. It is quite moving, and is considered by many to be one of the finest of modern conversion stories — some, in fact, have compared it to St. Augustine’s great autobiography, Confessions.

I read The Seven Storey Mountain during my early exploration of the Catholic faith and it made quite an impression, inspiring me to read many of his later works, most of which are primarily deep, mystical reflections on spirituality, Christ, the priesthood, and the contemplative life.

The Sign of Jonas picks up more or less where Mountain ends, a journal of Merton’s early years at Gesthemani. He describes events leading up to and surrounding the publication of Mountain, and the ensuing acclaim it brought him. A much larger story in his eyes, however, is his becoming a priest and the deep significance of that great calling.

(I discovered this book, incidentally, in a book by Bishop Robert Barron, Vibrant Paradoxes. He read The Sign of Jonas as a young man and it inspired him to become a priest — not surprisingly, I might add. Anyone discerning a priestly vocation or who is already a priest would find Jonas deeply meaningful and inspiring.)

At the beginning of Jonas, Merton is quite conflicted. He sees writing as a distraction from contemplation, and doesn’t really feel comfortable devoting so much time to it and receiving the attention publication brings to him. On the other hand, it is clear he enjoys writing deep in his bones, and has a great love of reading and collecting great works of spirituality — another task he is responsible for at Gesthemani. And while Merton acknowledges his love of writing and his fame thanks to Mountain, he clearly doesn’t think all that much of the quality of his own works.

Merton is also torn between remaining a Cistercian or leaving to become a Carthusian, another cloistered order even rigorous: whereas Cistercians live in a community, Carthusians live as hermits, far more isolated. Isolation, silence, complete withdrawal from the world are very appealing to Merton, and yet his work as a writer brings him in contact with the world to a degree otherwise unheard of in the Cistercian world.

As time goes on Merton comes to terms with these conflicts, to a great degree if not entirely. Joining the priesthood brings him tremendous peace of mind and peace of spirit, and brings his vocation into sharp focus. He shifts his attention from describing routine events of various days and the spiritual thoughts these events bring to mind; lengthier thoughts on theological, Biblical, and literary topics; and portraits of life at Gesthemani, his fellow Cistercians, and people he encounters in the outside world.

Some of these outside people are quite notable. The acerbic and idiosyncratic Evelyn Waugh (a renowned writer and man of letters) drops in at Gesthemani to meet Merton one day, making for an unusual and entertaining vignette. Merton corresponds with Clare Boothe Luce, and is friends with Robert Giroux and James Laughlin, and many other outstanding literary and religious figures of his day. Merton seems completely indifferent about these associations and his own status as a literary figure, which makes his commentary all the more fascinating.

The book is not without humor. While Merton is an intellectual par excellence, his motor skills are not always up to that same level. He drives a jeep into a ditch in the rain. (Although it must be noted that he had never driven a car before!) He continually fumbles with the various equipment used in the Mass and has trouble remembering the rubrics. Occasionally he even tells jokes, but usually they don’t quite hit the mark.

It’s good to know that even a person of Merton’s stature isn’t perfect. And Merton himself says he is far from perfect, in fact so far from perfect he wonders if he will ever become a contemplative in a way that is pleasing to God. And it is when Merton is reflecting on Christ and our relationship with Him that Merton is at his most mystical, profound, and illuminating — although I must confess that much of his mysticism is far beyond my understanding. For example:

“It seems to me that what I am made for is not speculation but silence and emptiness, to wait in the darkness and receive the Word of God entirely in His Oneness and not broken up into all His shadows.”

Or:

“And now – there is much more. Instead of myself and my Christ and my love and my prayer, there is the might of a prayer stronger than thunder and milder than the flight of doves rising up from the Priest who is the Center of the soul of every priest, shaking the foundations of the universe and lifting up – me, Host, altar, sanctuary, people, church, abbey, forest, cities, continents, seas, and worlds to God and plunging everything into Him.”

Beautiful. Meaningful. But what exactly does it mean? Someday I hope to have some kind of answer.

Fortunately, most of Jonas is much more accessible to the average reader. A few examples:

“Can’t I ever escape from being something comfortable and prosperous and smug? The world is terrible, people are starving to death and freezing and going to hell with despair and here I sit with a silver spoon in my mouth and write books and everybody sends me fan-mail telling me how wonderful I am for giving up so much. I’d like to ask them, what have I given up, anyway, except headaches and responsibilities?”

And:

“And this is at the root of the rejection of Christ – we do not really believe in Him because we want to believe only in ourselves, and we want to fabricate a basis for that belief by making other men praise us.”

And:

“It is not complicated, to lead the spiritual life. But it is difficult. We are blind, and subject to a thousand illusions. We must expect to be making mistakes almost all the time. We must be content to fall repeatedly and to begin again to try to deny ourselves, for the love of God.”

And:

“A saint is not so much a man who realizes that he possesses virtues and sanctity as one who is overwhelmed by the sanctity to God.”

And this is really what Jonas is about: One man’s struggle to become a saint. And isn’t this first and foremost what we should all be struggling to do? If Merton sees writing monumental works such as The Seven Storey Mountain and New Seeds of Contemplation as peripheral, what does this mean for us who all too often make God peripheral and things such as fame and fortune central?

Contemplative discipline such as that practiced by the Trappists is in part a means of avoiding distraction so that we can see God in everything. But we who live in the world are immersed in distraction. Reading Merton is a way to escape these distractions and gain a deeper appreciation of what it really means to be alive. Toward the end of the book Merton quotes a great line from Thoreau from Walden. I will leave you with it:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach me and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Further Reading

Abbey of Gesthemani

Evelyn Waugh

Clare Boothe Luce

Robert Giroux

James Laughlin

Bishop Robert Barron, Vibrant Paradoxes