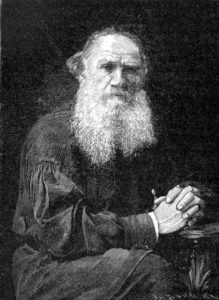

G.K. Chesterton and Leo Tolstoy have exerted enormous influence on thinking with regard to theology, philosophy, politics, economics, social organization, the arts, and science.

Both men considered themselves Christians, and both saw themselves as champions of the common man. And yet, it is hard to imagine two men more unlike in temperament and worldview.

Chesterton was cheerful. He could see humor in almost everything, and even his most ardent ideological opponents liked him personally. He had lots of friends and enjoyed a good time. Tolstoy was gloomy, seeing despair in almost everything. He was widely admired and had many ideological followers, but appears to have been rather lonely and aloof.

Chesterton was an orthodox Catholic — so much so that his most influential work is entitled, Orthodoxy. His fundamental solution to a multitude of problems was for people to live the Gospel: He said, “The Christian ideal has not been found wanting; it has been found difficult and not tried.” Tolstoy, in the sharpest contrast possible, rejected organized religion altogether, believing it to have been thoroughly and irretrievably corrupted. His was a Christianity without divinity, without revelation, without resurrection. He believed the only route to happiness was to revert to a more simple way of life.

Despite these differences, Chesterton and Tolstoy had a lot in common, besides their love of common people, They both believed concentration of wealth and power facilitated evil. They were both quick to point out and discredit artistic pretension and shallow thinking. They both saw the dire consequences of a culture rooted in materialism, relativism, and atheism.

Chesterton wrote an essay, Tolstoy and the Cult of Simplicity, which well describes his attitude toward Tolstoy’s way of thinking. It is persuasive. But then again, you may find, as I do, that many of Tolstoy’s observations and criticisms are spot on, despite their gloomy overtones. To get an idea of Tolstoy’s provocative viewpoint, read his Critical Essay on Shakespeare. (Tolstoy hated Shakespeare’s plays.)

Both Chesterton and Tolstoy are well worth reading today, because their insights, though a century old, are just as timely and necessary today as they were then. The fact they have stood the test of time gives evidence of the strength and truthfulness of their views.

Personally I’m drawn much more to Chesterton’s cure for what culturally ails us. But both men slap us in the face, alerting us to the serious dangers that confront us. These men are an antidote to apathy. And it is apathy, more than anything else, that puts us in danger.