Everyone knows our system of justice is based on the adversary system, in which two opposing advocates plead their case before an impartial judge. The advocates pull all the stops, within established ethical boundaries, to win their case. Out of this the vigorous clash of case making, it is thought that true justice will emerge.

This adversary system has worked its way into our political dialog, affecting how our elected officials, appointed officials, journalists and citizens talk to each other about every imaginable issue.

While the adversary system may work effectively in jurisprudence, it does not work well in political dialog. In law, the adversaries each represent a client. Their primary responsibility is to serve the interests of that client. But our elected representatives represent all of the citizens, not particular subsets of “clients” within their constituencies. Appointed officials as well answer to all citizens. Journalists and citizens are of course free to represent whomever they like, but if their primary motivation is advocacy rather than truth, where does that leave us?

It leaves us with a public square dominated by narratives.

- Narratives are spin.

- Narratives minimize or ignore facts that don’t align with the story and inflate facts that do.

- Narratives present an intentionally skewed version of reality masquerading as truth. Narratives are designed to deceive.

- Narratives are spun not to win arguments, but to marginalize opponents and inflate the confidence of supporters.

- Narratives build walls between two opposing camps rather than unite all people on some common ground — common ground that gets harder and harder to come by as narratives cover more and more terrain.

Narratives are becoming habitual in our culture — a cursory scan of any Twitter or Facebook stream should make that obvious.

The problem with narratives is twofold.

First, narratives make the more thoughtful among us skeptical of any source of information. This creates anxiety, uncertainty, and tends to freeze such people from judging or acting on any “facts” they may hear.

Second, narratives make the less thoughtful among us more certain of positions that are not as strong as they think them to be.

To the strongest narrative rather than to the strongest argument go the spoils.

Speaking of spoils, this seems to me to be the underlying reason for the explosion of narratives. Narratives are tactics to gain power. Just as attorneys formulate arguments to win cases, the rest of us formulate narratives to win causes.

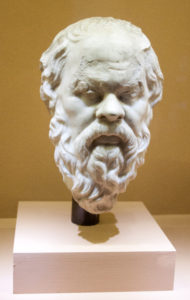

They say that Socrates refused to accept pay for his work, as he thought material gain would interfere with his search for truth. We could use a little more of that kind of thinking in our public square.

(Image credit – Wikimedia Commons)

Berrmot,

Important and insightful post. Thank you.

Bill