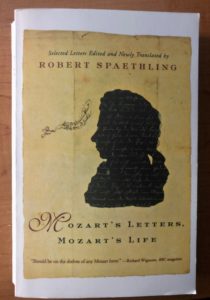

A Review of Mozart’s Letters, Mozart’s Life, Edited and Translated by Robert Spaethling

Studying a person’s letters is an excellent way to explore an individual’s life and personality, and Robert Spaethling’s edition of Wolfgang Mozart’s letters makes the experience especially rewarding. As the editor provides a preface to every letter, one need not be an expert on Mozart or musical history to make sense of the correspondence. Spaethling supplements the prefaces with brief but valuable footnotes that identify the compositions Mozart refers to and provide background on the people and events he writes about.

Studying a person’s letters is an excellent way to explore an individual’s life and personality, and Robert Spaethling’s edition of Wolfgang Mozart’s letters makes the experience especially rewarding. As the editor provides a preface to every letter, one need not be an expert on Mozart or musical history to make sense of the correspondence. Spaethling supplements the prefaces with brief but valuable footnotes that identify the compositions Mozart refers to and provide background on the people and events he writes about.

As to the letters themselves, Mozart comes across as a man with three very distinct sides: the hustling entrepreneur, the master musician, and the well-rounded human being. His letters begin in his early teens and end shortly before his death at age 35. Many of them are addressed to his beloved, demanding and sometimes cruel father, Leopold, an accomplished musician in his own right and the man most responsible for pushing his remarkable son to make the most of his prodigious talent. Wolfgang’s tone runs the gamut in his letters, from silly to confident to desperate (sometimes within the same letter) — but always, Mozart is likable, even when his faults are on full display.

Mozart the Entrepreneur

“… it’s my Wish and hope to gain Honor, Fame, and Money.” — To his father, from Vienna in 1781.

Mozart’s business talent was not equal to his musical talent. Mozart’s business goal was to to get hired by one of the royal courts of Europe. To these courts, music was seen as something of a commodity, and musicians were little more than hired hands. Mozart is continually angling to get an attractive, permanent paid position with a court. In pursuit of this, he gives away music to royal personages, cultivates relationships with key court influencers, dedicates compositions to the politically connected, and sells his music on the cheap in the hope it will lead to greater opportunities. Mozart always thinks he has the inside track, always assumes he’s going to get what he’s after. But almost every time, he mistakes flattery for real interest and ends up getting jerked around by the courts rather than being given serious consideration for a permanent position. It just goes to show that simply having a great product — in Mozart’s case, possibly the best music ever written — is not enough to ensure prosperity.

What’s most impressive about Mozart as entrepreneur is his resilience. Although disappointed when a business deal doesn’t work out, he bounces back in no time. He’s gets right back to work composing, and is just as enthused about the next deal as he was about the one that just came crashing down on his head. He never loses confidence in his musical ability, and despite his inability to land the dream job, does exceedingly well as a freelancer, enjoying widespread fame and the respect of fellow musicians throughout and beyond Europe. And for Mozart, that type of success meant more than the permanent, steady income he never enjoyed: His letters clearly reveal that what really got Mozart’s juices flowing was the acclaim of the crowd, of hearing people in the street humming his tunes and singing his arias.

Mozart the Musician

“I must not and cannot bury my Gift for Composing, that a benevolent God has bestowed upon me in such rich measure … I would rather … neglect the Clavier than Composition. For the Clavier is essentially a sideline for me, but, thank god, a very strong sideline … In the Wendling family they are all of the opinion that I would do extremely well with my Composition in Paris. I certainly am not worried about that, for I can, as you know, pretty much adopt and imitate any form and style of composition …” — To his father, from Mannheim in 1778.

Whereas Mozart the entrepreneur writes as a man struggling to be appreciated by the courts and often expressing frustration at their cheapness and lack of musical taste (among other things), Mozart the musician writes as a man who is not struggling in any way, expressing thoughts about music with the clarity and cool confidence that only a master could possess. He knows his compositions are the best in the world. He knows his gift is composing rather than teaching or playing clavier. He is quick to point out (with great accuracy and without pulling punches) the shortcomings of inferior composers, musicians, singers and librettists. On the other hand, he shows respect for other masters —Joseph Haydn, J.S. Bach and Handel are among the recipients of his praise — and he loves hanging out with his talented musical friends from the orchestra of the court of Mannheim, which was at the time the best and most innovative in all Europe.

“The thing isI have an inexpressible desire to write an opera again; … it would make me so happy because it gives me something to Compose which is my real joy and Passion …. whenever I hear people talk about an opera, whenever I’m in the theater and just hear the tuning of the instruments — oh, I get so excited, I’m totally beside myself … “ — To his father, from Munich in 1777.

Although his letters seldom describe the particulars of his creative process, there is one enormous exception: opera. Mozart frequently details his work in this medium, describing his struggles with librettists, singers, musicians and theater managers. Mozart had a deep understanding of drama and the varying tastes of audiences in, say, Paris, Vienna and Italy. Opera was Mozart’s favorite medium by far, probably because opera’s musical, lyrical, theatrical and collaborative elements challenged his talent in all areas. Opera was then the most popular form of musical entertainment, which was another attraction: Operas were the drivers of his popularity during his lifetime, as they were always well received and widely acclaimed.

Mozart valued versatility. He liked to talk about his ability to write all types of music (his expertise in sacred and concert music was a big selling point to the courts), and also his ability to adjust his music to fit the tastes of particular audiences, musicians and vocalists. If he wrote a piece for this pianist or that soprano, his music perfectly maximized that artist’s strengths and minimized the weaknesses — and it seems he could change gears from one composition to another as if he were merely changing shirts.

Mozart made no bones about it: he wanted to create music that people liked. No ivory tower, no “art for art’s sake” for Mozart. He thought music should be “natural” — easy on the ear, beautiful, inspiring, simple enough for the common person to enjoy and yet complex enough for the musical expert to savor. And in his letters, he conveys his ideas about music, profound as they are, in the simplest of words. It takes a true master to write in plain language, and Mozart seems to have had that ability in spades, which I suppose should come as no surprise considering his brilliance.

What’s most impressive about Mozart the musician is his clarity and intensity of purpose. By all accounts he was one of the best clavier players in all the world. He could have made a great living and won accolades in all quarters as a performer, and yet he knew that composing was his true calling and stuck with it, even though it caused him to suffer serious financial hardships and creative headaches all along the way. Mozart could take or leave teaching (in his letters he doesn’t sound like he enjoyed it much), and he probably would have been O.K. with not playing piano for audiences. But he could not live without composing. I suppose all great composers are similarly driven, and it’s lucky for us music lovers that such is the case.

Mozart the Man

“Congratulations! You are a Grandpapa! — Yesterday morning, the 17th, at half past six, my dear wife was safely delivered of a fine, sturdy boy, round as a butterball …” — To his father, from Vienna in 1783.

It’s through his letters that we can appreciate Mozart the man and come to understand why this most human of humans wrote music the way he did.

Although Mozart knew he was a musical genius, he struggled just like the rest of us in managing his life from day to day. And if he wrote about music with supreme confidence, when it came to writing about other aspects of his life, he conveyed the same doubts, frustrations and aspirations everyone feels. Mozart had his problems. He had a demanding father he could never please — but always wanted to. He was endlessly preoccupied with making ends meet. Towards the end of his life, his letters begging a friend for money are heart rending: his wife was sick, his medical expenses were out of control, and he always seemed to be just one big success away from hitting the financial jackpot. The jackpot never came. He could be arrogant, harsh, temperamental, short-tempered and vain. He could also be sympathetic, empathetic, encouraging, gentle and self-effacing.

He wanted to marry and be a good husband. He had six children with his wife, Constanze, but only two survived to adulthood (not an uncommon scenario in the 1700s). He could be a doting husband but also a jealous one. His devoted, beloved mother, standing in for Leopold, accompanied Mozart on a trip to Paris when he was a young man, and she unexpectedly died there of an illness. Most cruelly and unfairly, his father, who could not travel with him because of his job in Salzburg, let Wolfgang know that if he had been along with them in Paris, his mother would not have died. That sentiment goes far beyond the tough love that was Leopold’s specialty.

Two seemingly opposite tendencies seem to be at work in Mozart’s personality. On the one hand, he was a real joker. Letters from his teens and early twenties are full of puns, scatological humor, word games, funny anecdotes and offbeat observations. Flashes of humor shine through in his later letters as well, despite his being beset by one challenge after another and up to his eyeballs in work. And even on the job, he was not above pulling a prank in rehearsal or even during a performance, as he did on at least one occasion during The Magic Flute.

On the other hand, Mozart seemed genuinely intent on living a good, moral, honorable life. An observant Catholic, he frequently wrote about the importance of being a good man, of doing the right thing, of pleasing God as the first order of life’s business. To some extent, the letters to Leopold in which he expresses his religious seriousness may have been an effort to win approval, but I think Mozart stresses the theme too often and with too many correspondents for his piety to have been a mere act. Mozart liked to have a good time, but it does not seem that he was a drunk or a philanderer or a glutton.*

Thus in Mozart’s music we hear frivolity and awe, passion and intellect. Because Mozart was a man in the world and of the world, he could write in a world of styles, with a world of moods and experiences to draw on for inspiration. If you read these letters, along with Spaethling’s incredibly helpful notes, you may not only come to like Mozart as a person but also to appreciate him more deeply as a composer.

*In one letter he harshly criticized Michael Haydn, Joseph Haydn’s younger brother, for being drunk on the job as concertmaster in Salzburg. Mozart respected M. Haydn as a composer, but apparently not as a man.

(Image Credit – Wikimedia Commons)

It’s been quite some time since I’ve seen Amadeus (which was an amazing movie – probably on my top 5 of all time) so it may simply be that my memory fails me – but he comes across in your telling as a much more serious and respectful person than how he was portrayed in the movie.

This is great stuff Berrmot. Makes me want to read these letters myself.

Hi Greg, Thanks. I enjoyed Amadeus very much, but I recently read a music expert scorning the film because of its simplistic and distorted depiction of Mozart. Mozart’s letters demonstrate how right the expert is. Mozart definitely had a goofy streak, but he was so much more than that.

He sounds like a lot of today’s entrepreneur (or wantrepreneur) types, often looking for what’s impossible. But at least he understood there was power in networking. 🙂

True, Heidi. The courts may have disregarded him for a permanent position because of his young age and relatively low social standing, and also perhaps because he lacked experience and/or ability in management and political maneuvering. He wasn’t the only great composer to struggle financially, and some others fared much worse.