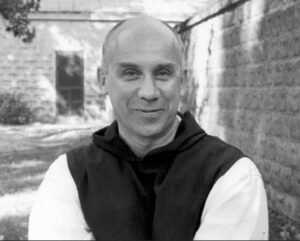

The Waters of Siloe, written by Thomas Merton in 1949, is the third of his works to be published after entering the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani, the first being his extraordinary autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, and the second being The Sign of Jonas, another largely autobiographical account of life in the cloister.

The Waters of Siloe, written by Thomas Merton in 1949, is the third of his works to be published after entering the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani, the first being his extraordinary autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, and the second being The Sign of Jonas, another largely autobiographical account of life in the cloister.

While Merton’s many other books that followed focus in a rather abstract way on contemplation and other aspects of Catholic mysticism and prayer, The Waters of Siloe presents a nuts-and-bolts history of the Cistercian order from its 12th-century roots to the modern day.

I was reluctant to even read this book, thinking, how interesting could 800 years of silent prayer, contemplation, and farming be?

Very, very interesting, as it turns out.

Merton describes how the lives of Trappist monks were far from an uninterrupted routine of prayer, penance, contemplation, and physical labor. Throughout their entire history they were persecuted, tortured, and slaughtered by Jacobins, Nazis, Communists, and many other Christ-hating governments. They were forced into exile, losing many brothers to disease and deprivation along the way to uncertain new homes. They ventured to the New World in search of hospitable land, again losing brothers along the way during months-long journeys taken under the worst possible conditions. During World Wars I and II, some were forced to fight or were taken prisoner — often losing their lives. And often they were forced away from their contemplative routine to provide schooling, nursing, and other worldly work because circumstances demanded it.

But in spite of all this, the Cistercians survived; in fact, every hardship made them stronger. In the worst of worldly times, many wanted to join them. It was in the best of worldly times that the Cistercians veered away from the Benedictine Rule and went into decline.

God works in mysterious ways.

Many have criticized Merton for indulging in writing rather than devoting himself fully to contemplation. After reading his history of the order, it becomes exceedingly difficult to hold this against him. Over many centuries Cistercians of the highest quality became outstanding explorers, pioneers, theologians, soldiers, and evangelists, because circumstances demanded it and these men had natural abilities that enabled them to serve God and men in other ways — although none of them ever abandoned their devotion to their monastic practices and principles. In fact, the way these men, and at times entire monastic communities, maintained their prayers and fasting in the face of enormous hardship is inspiring beyond measure. These men held Mass in concentration camps or with enemies at the gate. They could do this because the knew God loved them and they loved God with all their hearts and minds and souls.

The first three-quarters of Siloe is a straightforward history of the Cistercians, packed with facts but written, at times, in an almost poetic style. Merton has effusive praise for brothers (both prominent and obscure) whose work and sacrifices lifted the order, and delivers criticism of others in the most gentle way possible.

In the remainder of the book, Merton attempts to describe life in a Cistercian monastery in the 12th century. It is beautiful and utterly fascinating. He then concludes with an essay about the theological underpinnings of the Cistercian order and the contemplative life more generally. This essay, and all the other commentary on this topic Merton delves into throughout the book, are to me the clearest expression of these hard-to-grasp ideas he ever provided. Anyone interested in what contemplation is, what detachment means, what a monk’s role is in the the Body of Christ and in the world, why contemplative communities are important, why complete withdrawal from the world is crucial, and how a fruitful life of contemplation is achieved, will do himself great good by studying The Waters of Siloe.

Excerpts to give you a flavor of the book:

- About the founding of a Trappist monastery in New Mexico, Merton says, “The monks were bringing order to that peaceful valley. They were delivering it from the empty hearted restlessness of people with more money in their pockets than happiness in their souls. The deep and intelligent silence of contemplatives would now swallow up the last echo of the banal conversations that had once been heard in these groves. The hammers of carpenters and the sound of peaceful work would make those trees forget the dull noise of secular amusement, and the adolescent racket of third-rate swing music would be lost in the mature measures of Gregorian chant.”

- It was a long time before a native American became a successful American Trappist. “It was strange that the first native American to make a complete success of the Trappist life at Gethsemani should be a Texas cowboy.”

- About Armand de Rance (1626-1700), the colorful founder of the Trappists: “The walls were ready to fall down … The best-preserved place in the building was the refectory, which the monks now used as a bowling alley in wet weather. In the design of Providence, it was the commendatory abbot of this shambles who was to deliver the Cistercians from the threat of final and irreparable corruption and bring the Order from the edge of the grave back to life and health.”

- “The mentality of La Trappe was the mentality of a Lost Battalion, of a ‘suicide squad’ of men who knew they were doomed but were determined to go out of the world in grand style, making death and destruction pay so dearly for their triumph that death had no victory left at all.”

- Merton describes the thought of St. Bernard and the spirit of the Cistercian practice: “The one love that always grows weary of its object and is never satiated with anything and is always looking for something different and new is the love of ourselves. It is the source of all boredom and all restlessness and all unquiet and all misery and all unhappiness; ultimately, it is hell.”