Amundsen. Shackleton. Peary. Nansen. The pantheon of Arctic exploration is full of legends, but one you probably never heard of who belongs there is Valerian Albanov.

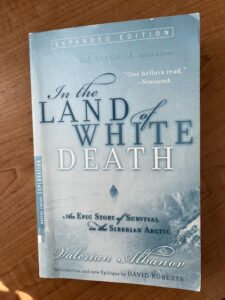

Although a big fan of Arctic exploration books, I had never heard of Albanov until I recently stumbled across his name in, of all places, Fr. Walter Ciszek’s With God in Russia. Fr. Ciszek, a prisoner in the Siberian salt mines, had heard of Albanov’s exploits while in Krasnoyarsk, where the explorer was quite a legend. And while Albanov is regarded as a hero throughout Russian (deserved so), he is virtually unknown in the U.S. Albanov’s account of his great adventure, In the Land of White Death, originally published in Russian in 1917, was not published in English until 2000.

Albanov was the navigator of the Brusilov Expedition of 1912, a very poorly organized and executed attempt to sail and map the North Sea Route, the eastern connecting route between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Of the 24 crew members of the Svyataya Anna, only two survived — Albanov and crewman Alexander Konrad, a stove-maker.

The commander of the expedition, Georgy Brusilov, was an inexperienced explorer and a mediocre leader at best. Before the ship sailed, there was a dispute of some kind that caused half the crew to walk off the job, forcing Brusilov to hire whatever able bodies he could find on the docks. Before long the ship was locked in the polar ice, drifting helplessly north. After a year and a half, with supplies running low and the chances of breaking free diminishing to zero, Albanov decided to travel via kayak and sledge across the ice floes in an effort to reach Cape Flora in Franz Josef Land, where there was thought to be a camp with shelter and supplies. To his surprise, 13 crewmen chose to go with him, while the rest clung to the ship hoping for a miraculous thaw.

The journey across the ice would last 90 harrowing days and cover 235 hard-fought miles. Albanov never wavered in his determination, although he was continually exasperated by the laziness and incompetence of the crewman with whom he was saddled. Fighting rough seas, frigid cold, blizzards, blistering winds, navigational equipment barely worth the name, dwindling food supplies, sickness, and finally, the desertion of two men who stole the lion’s share of what was left of their supplies — Albanov eventually reached his destination along with Konrad, the rest of the party having died along the way of sickness/starvation/causes unknown.

The journey across the ice would last 90 harrowing days and cover 235 hard-fought miles. Albanov never wavered in his determination, although he was continually exasperated by the laziness and incompetence of the crewman with whom he was saddled. Fighting rough seas, frigid cold, blizzards, blistering winds, navigational equipment barely worth the name, dwindling food supplies, sickness, and finally, the desertion of two men who stole the lion’s share of what was left of their supplies — Albanov eventually reached his destination along with Konrad, the rest of the party having died along the way of sickness/starvation/causes unknown.

Albanov’s account of the journey begins with his party leaving the Sveyataya Anna. It’s not very long, but just about every sentence packs a punch. Unlike many accounts of polar exploration, Albanov shares some of the crew’s dirty laundry, including some very critical comments about Brusilov, the crew, and even himself. Nevertheless, Albanov comes across as both fearless and compassionate. His overall assessment of Brusilov is charitable, and he puts his own life in jeopardy many times for the sake of crewmen who had been separated from the group or otherwise in danger.

The story is gripping on its own, but the afterword contains additional information and revelations which make the story even more amazing.

Eclectic and fascinating— as usual. Thanks

Thanks, Bill!